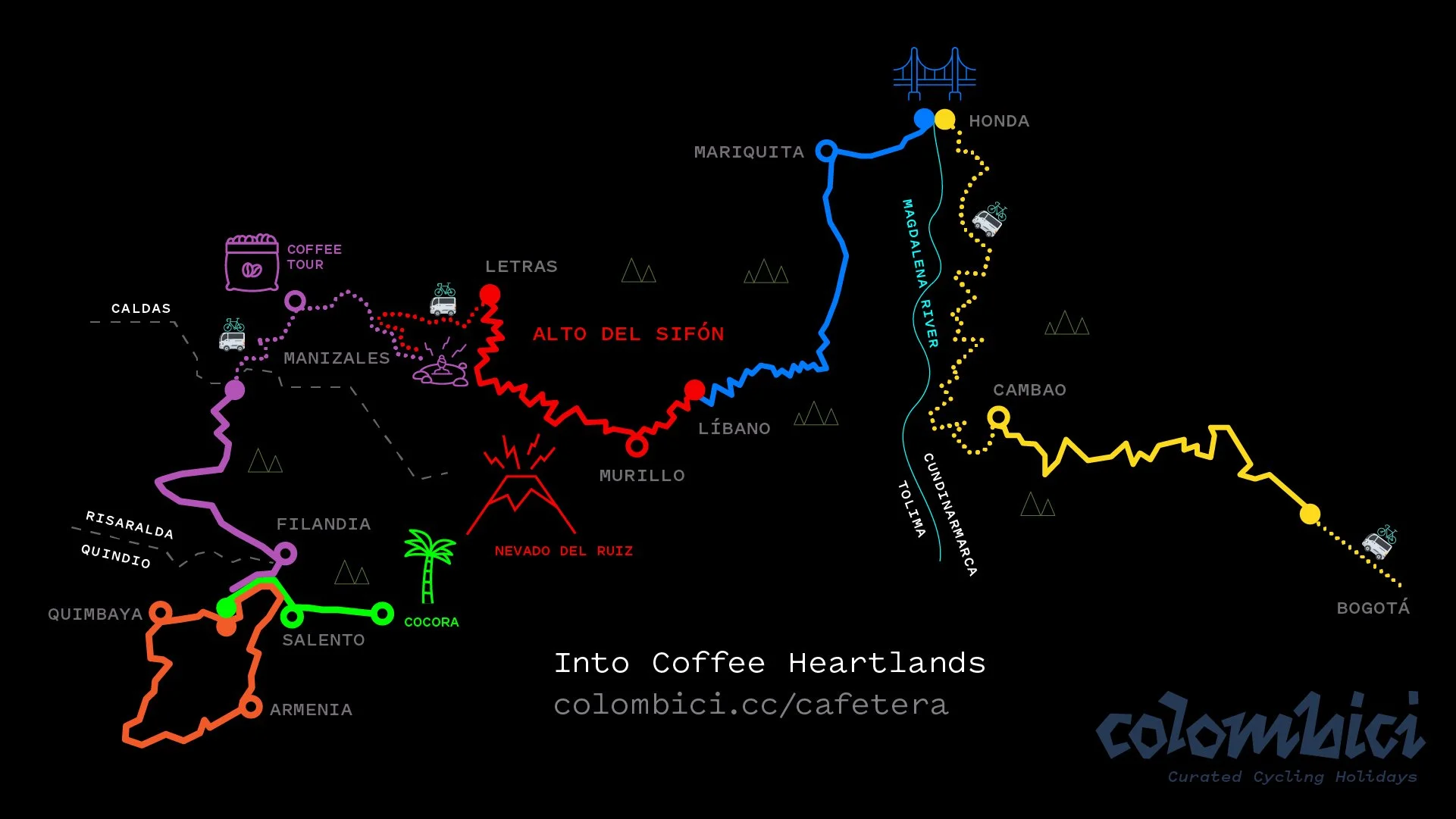

Into Colombia’s Coffee Heartlands and the Hidden Truths We Discovered

We originally planned our flagship tour around two things: climbs and coffee. But what we didn’t expect was how much more we’d discover along the way. Six days, five departments, and countless conversations later, we came home with stories that changed how we see Colombia and how we hope others will, too.

Photos by: Fotógrafo Alto de Letras

This journal is more than a tale of a tour. It’s our perspective from a curated route that climbed from 200 meters to over 4,100 meters through Colombia’s diverse landscapes. Along the way, we encountered the incredible people, from farmers to entrepreneurs, who are redefining Colombia’s identity through cycling, tourism, and sustainability. We witnessed the ambition of the youth, fragile ecosystems, and communities striving to balance progress with preservation. As these stories unfold, each one reveals a new facet of Colombia as it truly is today.

1. Dreams Aren’t Bound by 40 Bridges

We rolled into town on a Sunday evening. The air was thick with river humidity and the scent of frying maize. The clang of a distant church bell echoed through the narrow streets as dusk settled over Honda and its 40 bridges. The hot air and the scent of heavy gasoline and smoke clung to our jerseys. The main square is filled with kids racing in circles on their BMXs. The laughter was loud and unfiltered. One boy said he learned the tricks from YouTube. Another, barely taller than his handlebars, said he’d race in Europe one day. It wasn’t bragging. It was ambition.

In a region where unemployment hovers near 20 percent, the optimism feels radical. Most young people face a simple choice: leave for the city or stay to work locally. Yet these kids were already pedaling toward something bigger. Later that evening, a security guard at our hotel told us he’d learned English by watching Netflix. “Now I can talk to foreigners,” he said, smiling. It made us think. If the next generation speaks new languages, both literally and metaphorically, maybe Colombia’s next big story will be told by them.

2. The Price of Living in Paradise

From the muggy riverbanks of Honda, we set out on a long false-flat highway toward Mariquita, Armero, and into the mountains to Líbano. The road wound through plantain slopes, lulo and tomate de árbol fields, coffee scrubs, and foggy pine forests. We climbed from tropical lowlands into cooler Andean highlands. Two of us overheated and had to hop into the van. Not long after, the front group pulled on winter jackets and gloves.

This is Los Nevados National Natural Park, one of Colombia’s most fragile ecosystems, spanning Caldas, Quindío, Risaralda, and Tolima. The park is home to Colombia’s highest and northernmost active volcanoes, including Nevado del Ruiz. Protecting it requires strict development limits. Good for nature, but challenging for the people who live here.

In Líbano’s hospital, a nurse told us that even basic vaccines like rabies are sometimes unavailable. “You have to cross the mountain to get them,” she said, referring to a four-hour return trip by motorbike across cold, windy páramo terrain to Manizales, the nearest major medical facility. Supplies are unpredictable, the internet is patchy, and fuel deliveries depend on the weather. Yet she spoke without complaint, only calm resolve.

That conversation stayed with us. Our support van, loaded with food, water, and first-aid kits, stood outside as a reminder of privilege. What we see as an adventure is a daily reality for many here. It’s why our route passes through towns like Líbano and Murillo, to bridge visibility and connection, not just altitude.

Over breakfast in Murillo, a priest spooned soft cheese into his hot chocolate. “It’s the price of living in paradise,” he said. The real challenge is not choosing between preservation and progress. It is finding a way for both to coexist, so the people protecting paradise can flourish.

3. The Fragile Sleeping Lion

At 4,150 meters (13,615 feet) above sea level, we reached the climactic point of our journey, Alto el Sifón. The páramo was painted with rare frailejones, tall fuzzy-leaved plants that store water and sustain rivers for millions downstream. Colombia holds about half the world’s páramos. These plants grow a centimeter per year, and once damaged, take centuries to recover. Their forests create a fragile, high-altitude ecosystem unique to the northern Andes.

The climb through the páramo exposed us to extremes. One moment, we were battling heatstroke on the lower slopes, the next shivering near hypothermia as icy rain swept across the foggy highlands. Sustainable travel here is not a marketing slogan. It is survival. Tourism can raise awareness, but too much can harm what it aims to protect. Local guides now teach visitors how to respect the frailejones and the fragile wildlife.

Later, at the Termales hotel in Manizales, sitting at 3,800 meters (12,467 feet), we soaked in naturally heated pools fed by geothermal springs. The water, warm and mineral-rich, revealed a self-sustaining ecosystem where geology, water, and life exist seamlessly.

4. The Benefit and Burden of Being Famous

Descending from Manizales, roads narrowed into Colombia’s coffee triangle. Salento, once sleepy, is now one of the country’s most photographed towns. On weekends, the 3-kilometer climb into town turns into a traffic jam of Willys jeeps, scooters, and exhaust fumes. Tourism has brought prosperity, but also environmental pressure. Jeep exhaust lingers in the valley, and the Andean condor, Colombia’s national bird, is now rarely seen. Fewer than 150 condors remain nationwide. Drones are banned in Cocora Valley to protect wildlife.

Investments are mixed. Some come from locals, some from Bogotá, Medellín, and abroad. Even in crowded streets, quiet moments persist: locals cleaning the main square, children riding miniature Willys jeeps, and small roasters like Daniel Gomez, co-founder of Orígenes Café, offering export-quality beans domestically. For decades, Colombia’s best beans were shipped abroad while locals drank the leftovers. That is slowly changing. Young entrepreneurs roast locally, focusing on traceability, provenance, and fair pay. The lesson is simple. Tourism is not the problem. How we travel is.

5. Cycling, Community, and a New Chapter

Rolling green hills dotted with coffee trees and cows greet visitors in Filandia. The old ‘coffee highway’ is now rebranded as a cycling highway. At Casa du Vélo, a boutique cycling hotel run by Juan Pulido and his family, Laura, David, Felipe, and Miguel. They’re not just your hosts. They are ambassadors of a new Colombia, blending international standards with local soul. They promote sustainability, education, and responsible tourism, holding environmental permits to ensure the land, soil, and heritage remain for future generations.

Filandia demonstrates how tourism and coffee can support communities, preserve heritage, and create opportunities for the next generation. Here, cycling becomes more than a vehicle to progress. It is a way to celebrate, protect, and put Colombia on the world map as a cycling paradise.

6. A Country in Motion

Our journey through Colombia’s Coffee Heartlands began as a cycling adventure, but it became a lesson in perspective. Colombia is evolving, learning, and redefining itself. There are tensions and challenges, but also creativity, optimism, and belief.

At Colombici, responsible travel is built into how we operate. We stay in family-run hotels, eat where locals eat, and ride through towns that tourists have not found. Every stop, every coffee, supports someone along the route. The tours are designed to keep value in the communities that welcome us.

Colombia’s future will be shaped by everyday choices, where to grow, what to protect, and whose part of the story. The land may be fragile, but its people move forward with grit, care, and optimism. It’s that resilience, not the country’s old reputation for danger, that defines Colombia today.